Shark Week Presents: Katy Ayres

Today on Shark Week Presents, we catch up with shark scientist and PhD student Katy Ayres. Continue reading for Katy’s journey into marine biology and to discover how drones can be used in marine research.

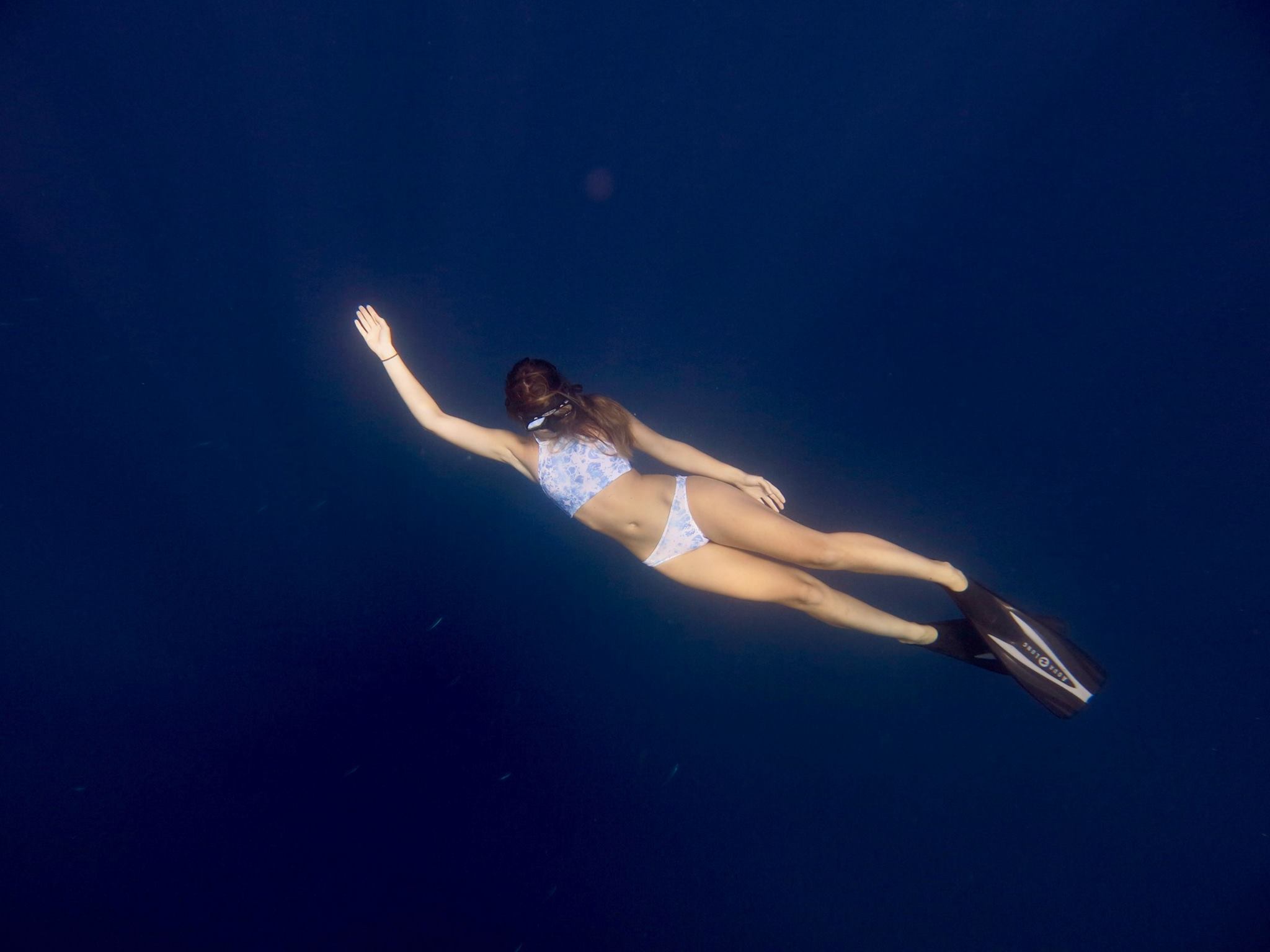

Katy with a silky shark

Hey Katy, thanks for coming on Shark Week Presents! Could you start off by telling us a little about you?

I am 27 years old and from a landlocked village in northern England. I have been obsessed with sharks all my life. My Grandma used to be a primary school teacher and she had many books. She gave me a sea life book and I became fixated with an image of a grey nurse shark with its many rows of long sharp teeth!

Once the internet arrived, I would spend hours researching information about sharks. I learned about shark fishing and the horrific activity of shark finning. I learned that there were relatively few shark attacks on humans and I knew then that sharks were not the monsters they were made out to be. It became my life’s ambition to learn as much as I could about these animals and to work in shark conservation to protect these amazing and beautiful creatures.

How did you become a shark scientist?

When I was 19 I deferred my university place in the UK to take a gap year. I travelled to Byron Bay in Australia to develop my diving skills. Diving with sharks everyday gave me a new found motivation to work hard for my BSc in Marine Vertebrate Zoology at Bangor University, North Wales, UK.

Following graduation I spent 2 years travelling including Fiji, New Zealand and the Galapagos Islands where through volunteering I gained invaluable fieldwork and project skills.

I returned to England to start a Masters in Marine Environmental Management at the University of York. My Masters thesis was based on data collected by an NGO called Pelagios Kakunja who work to study and protect shark species in Mexico. The following summer I did an internship in La Paz with this NGO. I wrote a proposal to return the following year to start a PhD. This is where I am now!

Could you tell us about your PhD?

My study site is a small 71km² area called Cabo Pulmo National Park located on the eastern coast of the Baja California peninsula. This area has been closed to fishing since 1995. It is a magical place and it is thriving with marine life – especially sharks.

Every week I pilot a drone along the coastline to count and record shark behaviours. My study species is the blacktip shark (Carcharhinus limbatus) and they group in their hundreds during the winter months. I also tag these sharks with acoustic transmitters and satellite tags to track their movements. Last year I became a National Geographic Explorer when I received an early career grant which allowed me to purchase tags and a drone for my study!

What have you learned from you PhD so far? What have the greatest challenges been?

Don’t give up and always have a plan B! Network and don’t be afraid to email researchers for advice. My PhD project heavily focuses on drone work and a very kind shark scientist in Florida lent me a drone before I received the grant to purchase my own.

The greatest challenge for me is studying in a country where the native language isn’t my own, I take Spanish lessons but I wish I had studied it earlier in my academic career. The best advice I could give to anyone who wants to work with sharks is to learn Spanish. There are many sharks in Latin America!

You’re currently in Baja California Sur. Tell us about the marine life we might find here.

It has everything! La Paz is well known for whale sharks and sea lions. You can snorkel with them in the winter season. In summer you can also swim with thousands of mobula rays, they famously jump out of the water and are spectacular. Many species of whales can be also be seen such as humpbacks and orcas and on the Pacific coast you can stroke grey whales from a boat – they actively seek out attention! The scuba diving is amazing too, you can see giant manta rays in summer and hammerhead sharks at the sea mounts, if you are lucky! We also have the Revillagigedo Archipelago off Cabo San Lucas one of the best dive sites in the world.

You’re also a droner! How can drones be used in marine (and shark) science?

I started my PhD without the drone element of my study. It is now the main focus. Drones are amazing. The data drones can provide is invaluable and it is non-invasive technique of collecting data on wild animals (you don’t have to touch them). Drones are commonly used for studying marine mammals, due to their large size and time spent on the surface breathing, as well as large sharks like whale and basking sharks. In certain areas, such as my study site, it is possible to film smaller sharks close to shore because they gather over sandy habitat making them highly visible.

As a shark scientist, what is your opinion on feeding sharks?

Shark feeding can be controversial. There is a school of thought that shark feeding alters behaviour. Whilst I agree that this can happen if feeding is not controlled, the argument is that these dives enable the public the opportunity to see sharks in the wild, to be educated and for the built respect for what are generally misunderstood animals. Shark tourism generates income for local economies and provides an alternative and incentive not to fish sharks, which are essential for ocean ecosystem health. In an ideal world we would not need to feed sharks but many species are at threat to extinction. Regulation, research and management are key to assessing the good and bad elements of shark feeding and this should be implemented at these dive sites, to make sure the activity is as safe for the sharks and divers as it can be.

Katy flying a drone

Let’s talk equality… What has your personal experience been as a woman in marine science?

I have been lucky, growing up with a twin brother and very supportive parents I have been told from a young age that I can do anything if I put my mind to it, regardless of my gender. It is great that women are working hands on in marine science and not just analysing data but are now at the forefront of the practical aspects, such as tagging sharks. I recently learned how to tag sharks internally (you make a small surgical incision and insert a tag) and I am happy with the support and encouragement I have had to tag the sharks myself. However, it’s not uncommon in many situations for people to doubt your abilities and when this happens you have to know your worth and not doubt yourself just because someone else does!

So how can we ensure that women and minorities are well-represented in marine science?

I think it is important for children from a young age to be encouraged and told that there is a place for them in marine science. It is also important to note that you don’t have to be a scientist to be able to work in conservation and science. This sector has many aspects and you might want to work with sharks but not be good or interested in experiments, but you might be good at telling stories or being creative. Communicating science and research to the public is very important and for many scientists it is not a skill that comes easily. Everyone has their qualities, from all backgrounds and genders, and these can be used across all aspects of science.

Financial support is key to ensuring inclusion. Studying, diving, travelling to volunteer are costly and could be a barrier to some minority groups taking that first step into marine science. Better funded scholarship programmes where travel costs are covered would be enabling.